BC’s Japanese Internment Camps

Photo: Unsourced, tumblr

Like most everywhere on the planet, Canada has its own abysmal history. Perhaps the darkest stain on our record occurred during the WWII Japanese internment.

Japanese persons began immigrating to Canada early in the 19th century – despite our blatant fear, racism and discrimination toward them.

At the time, we were also intolerant of Jewish persons, and persons of colour. These groups were banned from voting, and prevented from entering certain forms of employment. They were primarily ineligible for social assistance and all but barred from fishing and hunting.

The hope was that we would push the foreigners out, forcing them to return to their homeland.

Canada was so discriminatory against the Japanese, that we formed the The Anti-Asiatic League in 1907. Made up of primarily white business owners, the purpose of the ‘League’ was to force limits on Asian immigration.

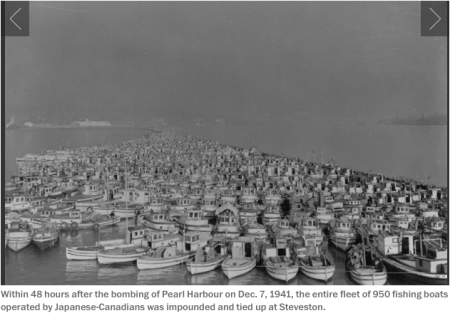

The Japanese were seen as fierce competition in agriculture and fishing sectors.

Photo source; http://comrademcbotbyl.tumblr.com

After the bombing of Pearl Harbour in January 1942, Japanese-Canadians were branded as enemy aliens under the War Measures Act.

On 14 January 1942, the government passed an order calling for the removal of male Japanese nationals 18 to 45 years of age from a designated ‘protected area’ 100 miles from the BC coast.

Photo: http://www.yesnet.yk.ca

At first, these men were primarily sent to ‘road camps’ throughout British Columbia.

Many men (and boys) perished from sickness and starvation while building roads connecting communities through rural mountainous BC.

Photo source: http://forums.castanet.net

Just three weeks after the first, another order was given to allow the removal of “all persons of Japanese origin”. At least 27,000 people were detained (women and children), and their property confiscated.

They were made to believe that their homes and valuables would be returned at the end of the war, but of course that did not happen.

Photo: http://www.windsorstar.com

Homes, fishing boats, vehicles, businesses – family heirlooms – everything. Taken and sold for a pittance to the local whites.

Photo: http://www.windsorstar.com

Men drove the family vehicles to a downtown Vancouver stadium, parked, handed their keys over to a white man, and entered the crowded, stinking stadium to wait with thousands of other Japanese to be taken away to camp.

Photo source: http://www.windsorstar.com

Many children were brought up in these camps, including famous Canadian environmental activist, David Suzuki. David was a third-generation Japanese-Canadian.

In June 1942, the government sold the Suzuki family’s dry-cleaning business, then interned Suzuki, his mother, and two sisters in a camp at Slocan in the British Columbian Interior.

Photo source: http://www.windsorstar.com

Not all men were sent to internment camps and road crews.

Some were shipped for labour on sugar beet farms in Taber, Alberta, others were sent to work on a logging operation near D’arcy, BC.

In the Lillooet valley, Japanese men found work on the railway, in local stores and on farms. In the Okanagan, they were put to work in the orchards.

Photo source: http://app.ufv.ca

Some lived in unsanitary stables and barnyards, through freezing winter – and hell hot summer. In a few cases, conditions were bad enough that the Red Cross stepped in and redirected food rations meant for Canadian civilians affected by the war, to the starving Japanese.

Various camps in the Lillooet area were labelled ”self-supporting projects” (or “relocation centres”). These housed middle and upper-class families deemed less a threat to public safety.

Though not technically ‘interned’, the Japanese here faced restrictions on their movement, but were able to live a somewhat ‘normal’ life with their families. They worked, operated shops and had children in school.

Photo from http://www.windsorstar.com

However, their children could only attend certain schools, and they could not leave the boundaries of the “relocation centre” without permission.

At the end of the war, interns were given a choice. Move east or go back to Japan. Many Japanese-Canadians (born in Canada), chose to head to Ontario – where they faced further discrimination.

There are many stories of successful business owners, teachers and doctors being forced to Ontario to work as farm hands – one of the few employment options they faced.

Other Canadian born Japanese were forced to relocate to Japan – an unfamiliar foreign place, with a language they didn’t speak, and food they had never eaten. Many stories have been written about this uncomfortable process.

Truly, Canada played a big hand in contributing to an already dark WWII history. Though we finally made apologies (by 1988) and nominal financial retribution (on-going) for our part in the former laceration of Canadian-Japanese life, in some cases, the wounds are still healing – and others will never mend.